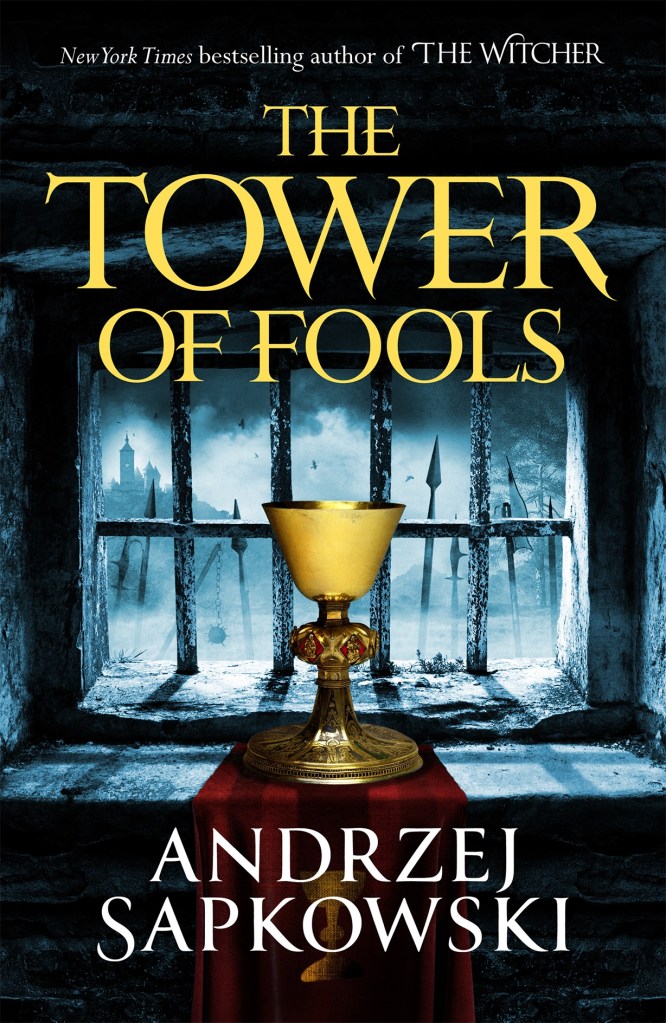

The Tower of Fools – an excerpt

The first in an epic new trilogy set during the vibrantly depicted Hussite Wars by Andrzej Sapkowski, author of the bestselling Witcher series that has become an international phenomenon and inspired a bestselling videogame and Netflix show.

Chapter One

In which the reader makes the acquaintance of Reinmar of Bielawa, called Reynevan, and of his better features, including his knowledge of the ars amandi, the arcana of horse-riding, and the Old Testament, though not necessarily in that order.

Through the small chamber’s window, against a background of the recently stormy sky, could be seen three towers. The first belonged to the town hall. Further off, the slender spire of the Church of Saint John the Evangelist, its shiny red tiles glistening in the sun. And beyond that, the round tower of the ducal castle. Swifts winged around the church spire, frightened by the recent tolling of the bells, the ozone-rich air still shuddering from the sound.

The bells had also quite recently tolled in the towers of the Churches of the Blessed Virgin Mary and Corpus Christi. Those towers, however, weren’t visible from the window of the chamber in the garret of a wooden building affixed like a swallow’s nest to the complex of the Augustinian hospice and priory.

It was time for Sext. The monks began the Deus in adjutoriumwhile Reinmar of Bielawa – known to his friends as ‘Reynevan’ – kissed the sweat-covered collarbone of Adele of Stercza, freed himself from her embrace and lay down beside her, panting, on bedclothes hot from lovemaking.

Outside, Priory Street echoed with shouts, the rattle of wagons, the dull thud of empty barrels and the melodious clanking of tin and copper pots. It was Wednesday, market day, which always attracted large numbers of merchants and customers.

Memento, salutis Auctor

quod nostri quondam corporis,

ex illibata Virgine

nascendo, formam sumpseris.

Maria mater gratiae,

mater misericordiae,

tu nos ab hoste protege,

et hora mortis suscipe . . .

They’re already singing the hymn, thought Reynevan, lazily embracing Adele, a native of distant Burgundy and the wife of the knight Gelfrad of Stercza. The hymn has begun. It beggars belief how swiftly moments of happiness pass. One wishes they would last for ever, but they fade like a fleeting dream.

‘Reynevan . . . Mon amour. . . My divine boy . . .’ Adele interrupted his dreamy reverie. She, too, was aware of the passing of time, but evidently had no intention of wasting it on philosophical deliberations.

Adele was utterly, completely, totally naked.

Every country has its customs,thought Reynevan. How fascinating it is to learn about the world and its peoples. Silesian and German women, for example, when they get down to it, never allow their shifts to be lifted higher than their navels. Polish and Czech women gladly lift theirs themselves, above their breasts, but not for all the world would they remove them completely. But Burgundians, oh, they cast off everything at once, their hot blood apparently unable to bear any cloth on their skin during the throes of passion. Ah, what a joy it is to learn about the world. The countryside of Burgundy must be beautiful. Lofty mountains . . . Steep hillsides . . . Vales . . .

‘Ah, aaah, mon amour,’ moaned Adele of Stercza, thrusting her entire Burgundian landscape against Reynevan’s hand.

Reynevan, incidentally, was twenty-three and quite lacking in worldly experience. He had known very few Czech women, even fewer Silesians and Germans, one Polish woman, one Romani, and had once been spurned by a Hungarian woman. Far from impressive, his erotic experiences were actually quite meagre in terms of both quantity and quality, but they still made him swell with pride and conceit. Reynevan – like every testosterone-fuelled young man – regarded himself as a great seducer and erotic connoisseur to whom the female race was an open book. The truth was that his eleven trysts with Adele of Stercza had taught Reynevan more about the ars amandi than his three-year studies in Prague. Reynevan hadn’t understood, however, that Adele was teaching him, certain that all that counted was his inborn talent.

Ad te levavi oculos meos

qui habitas in caelis.

Ecce sicut oculi servorum

In manibus dominorum suorum.

Sicut oculi ancillae in manibus dominae sua

ita oculi nostri ad Dominum Deum nostrum,

Donec misereatur nostri.

Miserere nostri Domine . . .

Adele seized Reynevan by the back of the neck and pulled him onto her. Reynevan, understanding what was required of him, made love to her powerfully and passionately, whispering assurances of devotion into her ear. He was happy. Very happy.

Reynevan owed the happiness intoxicating him to the Lord’s saints – indirectly, of course – as follows:

Feeling remorse for some sins or other – known only to himself and his confessor – the Silesian knight Gelfrad of Stercza had set off on a penitential pilgrimage to the grave of Saint James. But on the way, he decided that Compostela was definitely too far, and that a pilgrimage to Saint-Gilles would absolutely suffice. But Gelfrad wasn’t fated to reach Saint-Gilles, either. He only made it to Dijon, where by chance he met a sixteen-year-old Burgundian, the gorgeous Adele of Beauvoisin. Adele, who utterly enthralled Gelfrad with her beauty, was an orphan, and her two hell-raising and good-for-nothing brothers gave their sister to be married to the Silesian knight without a second thought. Although, in the brothers’ opinion, Silesia lay somewhere between the Tigris and the Euphrates, Stercza was the ideal brother-in-law in their eyes because he didn’t argue too much over the dowry. Thus, the Burgundian came to Heinrichsdorf, a village near Ziębice held in endowment by Gelfrad. While in Ziębice, Adele caught Reinmar of Bielawa’s eye. And vice versa.

‘Aaaah!’ screamed Adele of Stercza, wrapping her legs around Reynevan’s back. ‘Aaaaa-aaah!’

Never would those moans have occurred, and nothing more than surreptitious glances and furtive gestures have passed between them, if not for a third saint: George, to be precise. For on Saint George’s Day, Gelfrad of Stercza had sworn an oath and joined one of the many anti-Hussite crusades organised by the Brandenburg Prince-Elector and the Meissen margraves. The crusaders didn’t achieve any great victories – they entered Bohemia and left very soon after, not even risking a skirmish with the Hussites. But although there was no fighting, there were casualties, one of which turned out to be Gelfrad, who fractured his leg very badly falling from his horse and was still recuperating somewhere in Pleissnerland. Adele, a grass widow, staying in the meanwhile with her husband’s family in Bierut.w, was able to freely tryst with Reynevan in a chamber in the complex of the Augustinian priory in Oleśnica, not far from the hospice where Reynevan had his workshop.

The monks in the Church of Corpus Christi began to sing the second of three psalms making up the Sext. We’ll have to hurry, thought Reynevan. During the capitulum, at the latest the Kyrie, and not a moment after, Adele must vanish from the hospice. She cannot be

seen here.

Benedictus Dominus

qui non dedit nos

in captionem dentibus eorum.

Anima nostra sicut passer erepta est

de laqueo venantium . . .

Reynevan kissed Adele’s hip, and then, inspired by the monks’ singing, took a deep breath and plunged himself into her orchard of pomegranates. Adele tensed, straightened her arms and dug her fingers in his hair, augmenting his biblical initiatives with gentle movements of her hips.

‘Oh, oooooh . . . Mon amour. . . Mon magicien. . . My divine boy . . . My sorcerer . . .’

Qui confi dunt in Domino, sicut mons Sion

non commovebitur in aeternum,

qui habitat in Hierusalem . . .

The third already, thought Reynevan. How fleeting are these moments of happiness . . .

‘Revertere,’ he muttered, kneeling. ‘Turn around, turn around, Shulamith.’

Adele turned, knelt and leaned forward, seizing the Lindenwood planks of the bedhead tightly and presenting Reynevan with her entire ravishingly gorgeous posterior. Aphrodite Kallipygos, he thought, moving closer. The ancient association and erotic sight made him approach like the aforementioned Saint George, charging with his lance thrust out towards the dragon of Silene. Kneeling behind Adele like King Solomon behind the throne of wood of the cedar of Lebanon, he seized her vineyards of Engedi in both hands.

‘May I compare you, my love,’ he whispered, bent over a neck as shapely as the Tower of David, ‘may I compare you to a mare among Pharaoh’s chariots.’

And he did. Adele screamed through clenched teeth. Reynevan slowly slid his hands down her sides, slippery with sweat, and the Burgundian threw back her head like a mare about to clear a jump.

Gloria Patri, et Filio et Spiritui sancto.

Sicut erat in principio, et nunc, et semper

et in saecula saeculorum, Amen.

Alleluia!

As the monks concluded the Gloria, Reynevan, kissing the back of Adele of Stercza’s neck, placed his hand beneath her orchard of pomegranates, engrossed, mad, like a young hart skipping upon the mountains to his beloved . . .

A mailed fist struck the door, which thudded open with such force that the lock was torn off the frame and shot through the window like a meteor. Adele screamed shrilly as the Stercza brothers burst into the chamber.

Reynevan tumbled out of bed, positioning it between himself and the intruders, grabbed his clothes and began to hurriedly put them on. He largely succeeded, but only because the brothers Stercza had directed their frontal attack at their sister-in-law.

‘You vile harlot!’ bellowed Morold of Stercza, dragging a naked Adele from the bedclothes.

‘Wanton whore!’ chimed in Wittich, his older brother, while Wolfher – next oldest after Adele’s husband Gelfrad – did not even open his mouth, for pale fury had deprived him of speech. He struck Adele hard in the face. The Burgundian screamed. Wolfher struck her again, this time backhanded.

‘Don’t you dare hit her, Stercza!’ yelled Reynevan, but his voice broke and trembled with fear and a paralysing feeling of impotence, caused by his trousers being round his knees. ‘Don’t you dare!’

His cry achieved its effect, although not the way he had intended. Wolfher and Wittich, momentarily forgetting their adulterous sister-in-law, pounced on Reynevan, raining down a hail of punches and kicks on the boy. He cowered under the blows, but rather than defend or protect himself, he stubbornly pulled on his trousers as though they were some kind of magical armour. Out of the corner of one eye, he saw Wittich drawing a knife. Adele

screamed.

‘Don’t,’ Wolfher snapped at his brother. ‘Not here!’

Reynevan managed to get onto his knees. Wittich, face white with fury, jumped at him and punched him, throwing him to the floor again. Adele let out a piercing scream which broke off as Morold struck her in the face and pulled her hair.

‘Don’t you dare . . .’ Reynevan groaned ‘. . . hit her, you scoundrels!’

‘Bastard!’ yelled Wittich. ‘Just you wait!’

Wittich leaped forward, punched and kicked once and twice. Wolfher stopped him at the third.

‘Not here,’ Wolfher repeated calmly, but it was a baleful calm.

‘Into the courtyard with him. We’ll take him to Bierut.w. Th at slut, too.’

‘I’m innocent!’ wailed Adele of Stercza. ‘He bewitched me! Enchanted me! He’s a sorcerer! Sorcier! Diab—’

Morold silenced her with another punch. ‘Hold your tongue, trollop,’ he growled. ‘You’ll get the chance to scream. Just wait a while.’

‘Don’t you darehit her!’ yelled Reynevan.

‘We’ll give you a chance to scream, too, little rooster,’ Wolfher added, still menacingly calm. ‘Come on, out with him.’

The Stercza brothers threw Reynevan down the garret’s steep stairs and the boy tumbled onto the landing, splintering part of the wooden balustrade. Before he could get up, they seized him again and threw him out into the courtyard, onto sand strewn with steaming piles of horse shit.

‘Well, well, well,’ said Nicolaus of Stercza, the youngest of the brothers, barely a stripling, who was holding the horses. ‘Look who’s stopped by. Could it be Reinmar of Bielawa?’

‘The scholarly braggart Bielawa,’ snorted Jentsch of Knobelsdorf, known as Eagle Owl, a comrade and relative of the Sterczas. ‘The arrogant know-all Bielawa!’

‘Shitty poet,’ added Dieter Haxt, another friend of the family. ‘Bloody Abelard!’

‘And to prove to him we’re well read, too,’ said Wolfher as he descended the stairs, ‘we’ll do to him what they did to Abelard when he was caught with Heloise. Well, Bielawa? How do you fancy being a capon?’

‘Go fuck yourself, Stercza.

‘What? What?’ Although it seemed impossible, Wolfher Stercza had turned even paler. ‘The rooster still has the audacity to open his beak? To crow? Th e bullwhip, Jentsch!’

‘Don’t you dare beat him!’ Adele called impotently as she was led down the stairs, now clothed, albeit incompletely. ‘Don’t you dare! Or I’ll tell everyone what you are like! That you courted me yourself, pawed me and tried to debauch me behind your brother’s back! That you swore vengeance on me if I spurned you! Which is why you are so . . . so . . .

She couldn’t find the German word and the entire tirade fell apart. Wolfher just laughed.

‘Verily!’ he mocked. ‘People will listen to the Frenchwoman, the lewd strumpet. The bullwhip, Eagle Owl!’

The courtyard was suddenly awash with black Augustinian habits.

‘What is happening here?’ shouted the venerable Prior Erasmus Steinkeller, a bony and sallow old man. ‘Christians, what are you doing?’

‘Begone!’ bellowed Wolfher, cracking the bullwhip. ‘Begone, shaven-heads, hurry off to your prayer books! Don’t interfere in knightly affairs, or woe betide you, blackbacks!’

‘Good Lord.’ Th e prior put his liver-spotted hands together. ‘Forgive them, for they know not what they do. In nomine Patris, et Filii—’

‘Morold, Wittich!’ roared Wolfher. ‘Bring the harlot here! Jentsch, Dieter, bind her paramour!’

‘Or perhaps,’ snarled Stefan Rotkirch, another friend of the family who had been silent until then, ‘we’ll drag him behind a horse a little?’

‘We could. But first, we’ll give him a flogging!’

Wolfher aimed a blow with the horsewhip at the still-prone Reynevan but did not connect, as his wrist was seized by Brother Innocent, nicknamed by his fellow friars ‘Brother Insolent’, whose impressive height and build were apparent despite his humble monkish stoop. His vicelike grip held Wolfher’s arm motionless.

Stercza swore coarsely, jerked himself away and gave the monk a hard shove. But he might as well have shoved the tower in Oleśnica Castle for all the eff ect it had. Brother Innocent didn’t budge an inch. He shoved Wolfher back, propelling him halfway across the courtyard and dumping him in a pile of muck.

For a moment, there was silence. And then they all rushed the huge monk. Eagle Owl, the fi rst to attack, was punched in the teeth and tumbled across the sand. Morold of Stercza took a thump to the ear and staggered off to one side, staring vacantly. The others swarmed over the Augustinian like ants, raining blows on the monk’s huge form. Brother Insolent retaliated just as savagely and in a distinctly unchristian way, quite at odds with Saint Augustine’s rule of humility.

The sight enraged the old prior. He flushed like a beetroot, roared like a lion and rushed into the fray, striking left and right with heavy blows of his rosewood crucifix.

‘Pax!’ he bellowed as he struck. ‘Pax! Vobiscum! Love thy neighbour! Proximum tuum! Sicut te ipsum! Whoresons!’

Dieter Haxt punched him hard. The old man was flung over backwards and his sandals flew up, describing pretty trajectories in the air. The Augustinians cried out and several of them charged into battle, unable to restrain themselves. The courtyard was seething in earnest.

Wolfher of Stercza, who had been shoved out of the confusion, drew a short sword and brandished it – bloodshed looked inevitable. But Reynevan, who had finally managed to stand up, whacked him in the back of the head with the handle of the bullwhip he had picked up. Stercza held his head and turned around, only for Reynevan to lash him across the face. As Wolfher fell to the ground, Reynevan rushed towards the horses.

‘Adele! Here! To me!’

Adele didn’t even budge, and the indifference painted on her face was alarming. Reynevan leaped into the saddle. The horse neighed and fidgeted.

‘Adeeele!’

Morold, Wittich, Haxt and Eagle Owl were now running towards him. Reynevan reined the horse around, whistled piercingly and spurred it hard, making for the gate.

‘After him!’ yelled Wolfher. ‘To your horses and get after him!’

Reynevan’s first thought was to head towards Saint Mary’s Gate and out of the town into the woods, but the stretch of Cattle Street leading to the gate was totally crammed with wagons. Furthermore, the horse, urged on and frightened by the cries of an unfamiliar rider, was showing great individual initiative, so before he knew it, Reynevan was hurtling along at a gallop towards the town square, splashing mud and scattering passers-by. He didn’t have to look back to know the others were hot on his heels given the thudding of hooves, the neighing of horses, the angry roaring of the Sterczas and the furious yelling of people being jostled.

He jabbed the horse to a full gallop with his heels, hitting and knocking over a baker carrying a basket. A shower of loaves and pastries few into the mud, soon to be trodden beneath the hooves of the Sterczas’ horses. Reynevan didn’t even look back, more concerned with what was ahead of him than behind. A cart piled high with faggots of brushwood loomed up before his eyes. The cart was blocking almost the entire street, the rest of which was occupied by a group of half-clothed urchins, kneeling down and busily digging something extremely engrossing out of the muck.

‘We have you, Bielawa!’ thundered Wolfher from behind, also seeing the obstruction.

Reynevan’s horse was racing so swiftly there was no chance of stopping it. He pressed himself against its mane and closed his eyes. As a result, he didn’t see the half-naked children scatter with the speed and grace of rats. He didn’t look back, so nor did he see a peasant in a sheepskin jerkin turn around, somewhat stupefied, as he hauled a cart into the road. Nor did he see the Sterczas riding broadside into the cart. Nor Jentsch of Knobelsdorf soaring from the saddle and sweeping half of the faggots from the cart with his body.

Reynevan galloped down Saint John’s Street, between the town hall and the burgermeister’s house, hurtling at full speed into Oleśnica’s huge and crowded town square. Pandemonium erupted. Aiming for the southern frontage and the squat, square tower of the Oława Gate visible above it, Reynevan galloped through the crowds, leaving havoc behind him. Townsfolk yelled and pigs squealed, as overturned stalls and benches showered a hail of household goods and foodstuff s of every kind in all directions. Clouds of feathers flew everywhere as the Sterczas – hot on Reynevan’s heels – added to the destruction.

Reynevan’s horse, frightened by a goose flying past its nose, recoiled and hurtled into a fish stall, shattering crates and bursting open barrels. Th e enraged fishmonger made a great swipe with a keep net, missing Reynevan but striking the horse’s rump. The horse whinnied and slewed sideways, upending a stall selling thread and ribbons, and only a miracle prevented Reynevan from falling. Out of the corner of one eye, he saw the stallholder running after him brandishing a huge cleaver (serving God only knew what purpose in the haberdashery trade). Spitting out some goose feathers stuck to his lips, he brought the horse under control and galloped through the shambles, knowing that the Oława Gate was very close.

‘I’ll tear your balls off , Bielawa!’ Wolfher of Stercza roared from behind. ‘I’ll tear them off and stuff them down your throat!’

‘Kiss my arse!’

Only four men were chasing him now – Rotkirch had been pulled from his horse and was being roughed up by some infuriated market traders.

Reynevan darted like an arrow down an avenue of animal carcasses suspended by their legs. Most of the butchers leaped back in alarm, but one carrying a large haunch of beef on one shoulder tumbled under the hooves of Wittich’s horse, which took fright, reared up and was ploughed into by Wolfher’s horse. Wittich few from the saddle straight onto the meat stall, nose-first into livers, lights and kidneys, and was then landed on by Wolfher. His foot was caught in the stirrup and before he could free himself, he had smashed a large number of stalls and covered himself in mud and blood.

At the last moment, Reynevan quickly lowered his head over the horse’s neck to duck under a wooden sign with a piglet’s head painted on it. Dieter Haxt, who was bearing down on him, wasn’t quick enough and the cheerfully grinning piglet slammed into his forehead. Dieter flew from the saddle and crashed into a pile of refuse, frightening some cats. Reynevan turned around. Now only Nicolaus of Stercza was keeping up with him.

Reynevan shot out of the chaos at a full gallop and into a small square where some tanners were working. As a frame hung with wet hides loomed up before him, he urged his horse to jump. It did. And Reynevan didn’t fall off. Another miracle.

Nicolaus wasn’t as lucky. His horse skidded to a halt in front of the frame and collided with it, slipping on the mud and scraps of meat and fat. Th e youngest Stercza shot over his horse’s head, with very unfortunate results. He flew belly-first right onto a scythe used for scraping leather which the tanners had left propped up against the frame.

At first, Nicolaus had no idea what had happened. He got up from the ground, caught hold of his horse, and only when it snorted and stepped back did his knees sag and buckle beneath him. Still not really knowing what was happening, the youngest Stercza slid across the mud after the panicked horse, which was still moving back and snorting. Finally, as he released the reins and tried to get to his feet again, he realised something was wrong and looked down at his midriff.

And screamed.

He dropped to his knees in the middle of a rapidly spreading pool of blood. Dieter Haxt rode up, reined in his horse and dismounted. A moment later, Wolfher and Wittich followed suit. Nicolaus sat down heavily. Looked at his belly again. Screamed and then burst into tears. His eyes began to glaze over as the blood gushing from him mingled with the blood of the oxen and hogs butchered that morning.

‘Nicolaaaaus!’ yelled Wolfher.

Nicolaus of Stercza coughed and choked. And died.

‘You are dead, Reinmar of Bielawa!’ Wolfher of Stercza, pale with fury, bellowed towards the gate. ‘I’ll catch you, kill you, destroy you. Exterminate you and your entire viperous family. Your entire viperous family, do you hear?’

Reynevan didn’t. Amid the thud of horseshoes on the bridge planks, he was leaving Oleśnica and dashing south, straight for the Wrocław highway.

Chapter Two

In which the reader finds out more about Reynevan from conversations involving various people, some kindly disposed and others quite the opposite. Meanwhile, Reynevan himself is wandering around the woods near Oleśnica. Th e author is sparing in his descriptions of that trek, hence the reader – nolens volens– will have to imagine it.

‘Sit you down, gentlemen,’ said Bartłomiej Sachs, the burgermeister of Oleśnica, to the councillors. ‘What’s your pleasure? Truth be told, I have no wines to regale you with. But ale, ho-ho, today I was brought some excellent matured ale, fi rst brew, from a deep, cold cellar in Świdnica.’

‘Beer it is, then, Master Bartłomiej,’ said Jan Hofrichter, one of the town’s wealthiest merchants, rubbing his hands together. ‘Ale is our tipple, let the nobility and diverse lordlings pickle their guts in wine . . . With my apologies, Reverend . . .’

‘Not at all,’ replied Father Jakub of Gall, parish priest at the Church of Saint John the Evangelist. ‘I’m no longer a nobleman, I’m a parson. And a parson, naturally, is ever with his flock, thus it doesn’t behove me to disdain beer. And I may drink, for Vespers have been said.’

They sat down at the table in the huge, low-ceilinged, whitewashed chamber of the town hall, the usual location for meetings of the town council. The burgermeister was in his customary seat, backto the fireplace, with Father Gall beside him, facing the window. Opposite sat Hofrichter, beside him Łukasz Friedmann, a soughtafter and wealthy goldsmith, in his fashionably padded doublet, a velvet beret resting on curled hair, every inch the nobleman.

The burgermeister cleared his throat and began, without waiting for the servant to bring the beer. ‘And what is this?’ he said, linking his hands on his prominent belly. ‘What have the noble knights treated us to in our town? A brawl at the Augustinian priory. A chase on horseback through the streets. A disturbance in the town square, several folk injured, including one child gravely. Belongings destroyed, goods marred – such significant material losses that mercatores et institores were pestering me for hours with demands for compensation. In sooth, I ought to pack them off with their plaints to the Lords Stercza!’

‘Better not,’ Jan Hofrichter advised dryly. ‘Though I also hold that our noblemen have been lately passing unruly, one can neither forget the causes of the affair nor of its consequences. For the consequence – the tragic consequence – is the death of young Nicolaus of Stercza. And the cause: licentiousness and debauchery. The Sterczas were defending their brother’s honour, pursuing the adulterer who seduced their sister-in-law and besmirched the marital bed. In truth, in their zeal they overplayed a touch—’

The merchant stopped speaking under Father Jakub’s telling gaze. For when Father Jakub signalled with a look his desire to express himself, even the burgermeister himself fell silent. Jakub Gall was not only the parish priest of the town’s church, but also secretary to Konrad, Duke of Oleśnica, and canon in the Chapter of Wrocław Cathedral.

‘Adultery is a sin,’ intoned the priest, straightening his skinny frame behind the table. ‘Adultery is also a crime. But God punishes sins and the law punishes crimes. Nothing justifies mob law and killings.’

‘Yes, yes,’ agreed the burgermeister, but fell silent at once and devoted all his attention to the beer that had just arrived.

‘Nicolaus of Stercza died tragically, which pains us greatly,’ added Father Gall, ‘but as the result of an accident. However, had Wolfher and company caught Reinmar of Bielawa, we would be dealing with a murder in our jurisdiction. We know not if there might yet be one. Let me remind you that Prior Steinkeller, the pious old man severely beaten by the Sterczas, is lying as if lifeless in the Augustinian priory. If he expires as a result of the beating, there’ll be a problem. For the Sterczas, to be precise.’

‘Whereas, regarding the crime of adultery,’ said the goldsmith Łukasz Friedmann, examining the rings on his manicured fingers, ‘mark, honourable gentlemen, that it is not our jurisdiction at all.

Although the debauchery occurred in Oleśnica, the culprits do not come under our authority. Gelfrad of Stercza, the cuckolded husband, is a vassal of the Duke of Ziębice. As is the seducer, the young physician, Reinmar of Bielawa—’

‘The debauchery took place here, as did the crime,’ said Hofrichter firmly. ‘And it was a serious one, if we are to believe what Stercza’s wife disclosed at the Augustinian priory – that the physician beguiled her with spells and used sorcery to entice her to sin. He compelled her against her will.’

‘That’s what they all say,’ the burgermeister boomed from the depths of his mug.

‘Particularly when someone of Wolfher of Stercza’s ilk holds a knife to their throat,’ the goldsmith added without emotion.

‘The Reverend Father Jakub was right to say that adultery is a felony – a crimen – and as such demands an investigation and a trial. We do not wish for familial vendettas or street brawls. We shall not allow enraged lordlings to raise a hand against men of the cloth, wield knives or trample people in city squares. In Świdnica, a Pannewitz went to the tower for striking an armourer and threatening him with a dagger. Which is proper. The times of knightly licence must not return. Th e case must go before the duke.’

‘All the more so since Reinmar of Bielawa is a nobleman and Adele of Stercza a noblewoman,’ the burgermeister confirmed with a nod. ‘We cannot fl og him, nor banish her from the town like a common harlot. Th e case must come before the duke.’

‘Let’s not be too hasty with this,’ said Father Gall, gazing at the ceiling. ‘Duke Konrad is preparing to travel to Wrocław and has a multitude of matters to deal with before his departure. The rumours have probably already reached him – as rumours do – but now isn’t the time to make them official. Suffice it to postpone the matter until his return. Much may be resolved by then.’

‘I concur.’ Bartłomiej Sachs nodded again.

‘As do I,’ added the goldsmith.

Jan Hofrichter straightened his marten-fur calpac and blew the froth from his mug. ‘For the present, we ought not to inform the duke,’ he pronounced. ‘We shall wait until he returns, I agree with you on that, honourable gentlemen. But we must inform the Holy Office, and fast, about what we found in the physician’s workshop. Don’t shake your head, Master Bartłomiej, or make faces, honourable Master Łukasz. And you, Reverend, stop sighing and counting flies on the ceiling. I desire this about as much as you do, and the same goes for the Inquisition. But many were present at the opening of the workshop. And where there are many people, at least one of them is reporting back to the Inquisition. And when the Inquisitor arrives in Oleśnica, we’ll be the first to be asked why we delayed.’

‘So I will explain the delay,’ said Father Gall, tearing his attention away from the ceiling. ‘I, in person, because it’s my parish and the responsibility to inform the bishop and the papal Inquisitor falls on me. It is also for me to judge whether the circumstances justify the summoning and bothering of the Curia and the Office.’

‘Isn’t the witchcraft that Adele of Stercza was screaming about at the Augustinian priory a circumstance?’ persisted Jan Hofrichter.

‘Isn’t the workshop itself? Aren’t the alchemic alembic and pentagram on the floor? The mandrake? Th e skulls and skeletons’ hands? The crystals and looking glasses? The bottles and flacons containing the Devil only knows what fi lth and venom? Th e frogs and lizards in specimen jars? Aren’t they circumstances?’

‘They are not,’ said Father Gall. ‘Th e Inquisitors are serious men. What interests them is inquisitio de articulis fi dei, not old wives’ tales, superstitions and frogs. I have no intention of bothering them with that.’

‘And the books?’ said Hofrichter. ‘The ones we have here?’

‘The books ought first to be examined,’ replied Jakub Gall calmly.

‘Thoroughly and unhurriedly. The Holy Office doesn’t forbid reading. Nor the owning of books.’

‘Two people have just gone to the stake in Wrocław,’ Hofrichter said gloomily, ‘for owning a book, or so the rumour runs.’

‘Not for owning books,’ the parish priest countered dryly, ‘but for contempt of court, for an impertinent refusal to renounce the content propagated in those books, among which were the writings of Wycliffe and Huss, the Lollard Floretus, the Articles of Prague and numerous other Hussite pamphlets and tracts. I don’t see anything like that here, among the books confiscated from Reinmar of Bielawa’s workshop. I see almost exclusively medical tomes. Which, as a matter of fact, are mainly or even entirely the property of the Augustinian priory’s scriptorium.’

‘I repeat,’ Jan Hofrichter stood up and went over to the books spread out on the table, ‘I repeat, I am not at all keen to involve either the bishop or the papal Inquisition – I don’t wish to denounce anyone or see anyone sizzling at the stake. But this concerns our arses and ensuring that we aren’t accused of possessing these books, either. And what do we have here? Apart from Galen, Pliny and Strabo? Albertus Magnus, De vegetabilis et plantis. . . Magnus, ha, a nickname right worthy of a wizard. And here, well, well, Shapur ibn Sahl . . . Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi . . . Pagans! Saracens!’

‘The works of these Saracens are taught at Christian universities,’ Łukasz Friedmann calmly explained, examining his rings, ‘as medical authorities. And your “wizard” is Albert the Great, the Bishop of Regensburg, a learned theologian.’

‘You don’t say? Hmmm . . . Let’s keep looking . . . See! Causae et curae, written by Hildegard of Bingen. Undoubtedly a witch, that Hildegard!’

‘Not really,’ Father Gall said, smiling. ‘Hildegard of Bingen, a visionary, called the Sibyl of the Rhine. She died in an aura of saintliness.’

‘If you say so . . . But what’s this? John Gerard, A Generall. . . Historie . . . of Plantes . . .I wonder what tongue this is. Hebrew, perhaps. But he’s probably another saint. And here we have Herbarius, by Thomas of Bohemia—’

‘What did you say?’ Father Jakub lifted his head. ‘Thomas of Bohemia?’

‘That’s what is written here.’

‘Show me. Hmmm . . . Interesting, interesting . . . Everything, it turns out, remains in the family. And revolves around the family.’

‘What family?’

‘So close to home, it couldn’t be closer.’ Łukasz Friedmann still appeared to be utterly absorbed by his rings. ‘Thomas of Bohemia is the great-grandfather of our Reinmar, the lover of other men’s wives, the man who has caused us such confusion and trouble.’

‘Thomas of Bohemia . . .’ The burgermeister frowned. ‘Also called Thomas the Physician. I’ve heard of him. He was a companion of one of the dukes . . . I can’t recall which . . .’

‘Duke Henry VI of Wrocław,’ Friedmann the goldsmith calmly offered in explanation.

‘It is also said,’ Hofrichter interrupted, nodding in confirmation, ‘that he was a wizard and a heretic.’

‘You’re worrying that sorcery like a bone, Master Jan,’ the burgermeister said with a grimace. ‘Let it go.’

‘Thomas of Bohemia was a man of the cloth,’ the priest informed them in a slightly harsh voice, ‘a canon in Wrocław and later a diocesan suffragan bishop and the titular Bishop of Zarephath. He knew Pope Benedict XII personally.’

‘All sorts of things were said about thatpope,’ added Hofrichter, not letting up. ‘And witchcraft occurred among protonotaries apostolic, too. When in offi ce, Inquisitor Schwenckefeld—’

‘Just drop it, would you,’ Father Jakub said, cutting him off . ‘We have other concerns here.’

‘Indeed,’ confirmed the goldsmith. ‘And I know what they are. Duke Henry had no male issue, but three daughters. Our Father Thomas of Bohemia took the liberty of a dalliance with the youngest, Margaret.’

‘The duke permitted it?’ Hofrichter asked. ‘Were they such good friends?’

‘The duke was dead by then,’ the goldsmith explained, ‘so Duchess Anne either didn’t see it or chose not to. Although not yet a bishop, Thomas of Bohemia was on excellent terms with the other nobles of Silesia. For imagine, gentlemen, somebody who not only visits the Holy Father in Avignon, but is also capable of removing kidney stones so skilfully that after the operation, the patient doesn’t just still have a prick – he can even get it up. It is widely believed that it is thanks to Thomas that we still have Piasts in Silesia today. He aided both men and women with equal skill. And couples, too, if you understand my meaning.’

‘I fear I do not,’ said the burgermeister.

‘He was able to help married couples who were unsuccessful in the bedchamber. Now do you understand?’

‘Now I do.’ Jan Hofrichter nodded. ‘So, he probably bedded the Wrocław princess according to medical principles, too. Of course, there was issue from that.’

‘Naturally,’ replied Father Jakub, ‘and the matter was dealt with in the usual way. Margaret was sent to the Poor Clares convent and the child, Tymo, ended up with Duke Konrad in Oleśnica, who raised him as his own. Thomas of Bohemia grew in importance everywhere, in Silesia and at the court of Charles IV in Prague, so the boy had a career guaranteed from childhood onwards – an ecclesiastical career, naturally, all dependent on what kind of intelligence he displayed. Were he dim, he’d become a village priest. Were he reasonably bright, he’d be made an abbot in a Cistercian monastery somewhere. Were he intelligent, a chapter of one of the collegiates would be waiting for him.’

‘How did he turn out?’ Hofrichter asked.

‘Quite bright. Handsome, like his father. And valiant. As a young man, the future priest fought against the Greater Poles beside the younger duke, the future Konrad the Elder. He fought so bravely that nothing was left but to dub him a knight and grant him a fiefdom. And thus, the young priest Tymo was dead, and long live Sir Tymo Behem of Bielawa. Sir Tymo, who soon became even better connected by wedding the youngest daughter of Heidenreich Nostitz, from which union Henryk and Tomasz were born. Henryk took holy orders, was educated in Prague and until his quite recent death was the scholaster at the Church of the Holy Cross in Wrocław. Tomasz, meanwhile, wedded Boguszka, the daughter of Miksza of Prochowice, who bore him two children, Piotr and Reinmar, this Reynevan who is causing us so much trouble.’ Jan Hofrichter nodded and sipped beer from his mug. ‘And this Reinmar-Reynevan who’s in the habit of seducing other men’s wives . . . what is his position at the Augustinian priory? An oblatus? A conversus? A novice?’

‘Reinmar of Bielawa,’ Father Jakub said, smiling, ‘is a physician, schooled at Charles University in Prague. Before that, the boy attended the cathedral school in Wrocław, then learned the arcana of herbalism from the apothecaries of Świdnica and the monks of the monastery of the Hospital of the Holy Ghost in Brzeg. It was those monks and his uncle Henryk, the Wrocław scholaster, who placed him with the Augustinians, who are skilled in herbalism. The boy worked honestly and eagerly in the hospital and the leper house, proving his vocation. Later on, he studied medicine in Prague, again benefi tting from his uncle’s patronage and the money his uncle received from the canonry. He clearly applied himself to his studies, for after two short years he was a Bachelor of Arts. He left Prague right after the . . . erm—’

‘Right after the Defenestration,’ the burgermeister said, undaunted.

‘Which clearly shows he had nothing in common with Hussite heresy.’

‘Nothing links him with it,’ Friedmann the goldsmith calmly confirmed. ‘Which I know from my son, who also studied in Prague at the same time.’

‘It was also very fortunate,’ added Burgermeister Sachs, ‘that Reynevan returned to Silesia, and to us, in Oleśnica, and not to the Ziębice duchy, where his brother Piotr serves Duke Jan as a knight. Reynevan is a good and bright lad, though young, and so able at herbalism that you’d be hard-pressed to fi nd his equal. He treated the carbuncles that appeared on my wife’s . . . body, and cured my daughter’s chronic cough. He gave me a decoction for my suppurating eyes, which cleared up as if by magic . . .’ The burgermeister fell silent, cleared his throat and shoved his hands into the furtrimmed sleeves of his coat.

Jan Hofrichter looked at him keenly. ‘Now all is clear to me about this Reynevan,’ he fi nally pronounced, ‘I know everything. Misbegotten, albeit, but of Piast blood. A bishop’s son. A favourite of dukes. Kin of the Nostitz family. The nephew of the scholaster at Wrocław Collegiate Church. A friend of rich men’s sons at university. On top of that, as if that weren’t enough, a conscientious physician, almost a miracle worker, capable of winning the gratitude of the powerful. And of what did he cure you, Reverend Father Jakub? From what complaint, out of interest?’

‘The complaint,’ the parish priest said coldly, ‘is no subject for discussion. Let’s just say that he cured me.’

‘It’s not worth the worry of executing somebody like that,’ added the burgermeister. ‘It’d be a shame to let such a lad perish in a family feud, just because his head was turned by a pair of beautiful. . . eyes. Let him serve folk. Let him treat folk, since he is skilled—’

‘Even by using a pentagram drawn on the fl oor?’ snorted Hofrichter.

‘If it works,’ said Father Gall gravely, ‘if it helps, if it eases the pain, why not? Such abilities are divine gifts; the Lord gives them according to His will and according to designs known only to Him. Spiritus fiat, ubi vult, it’s not for us to question His ways.’

‘Amen,’ concluded the burgermeister.

‘In short,’ Hofrichter kept pushing, ‘someone like Reynevan cannot be guilty? Is that it? Eh?’

‘He who is without guilt,’ Father Gall replied inscrutably, ‘let him cast the first stone. And God will judge us all.’

For a while, such a pregnant silence reigned that the rustle of moths’ wings striking the window could be heard. The longdrawn-out and melodious call of the town guard was audible from Saint John’s Street.

‘Wherefore, to summarise,’ said the burgermeister, sitting up straight at the table so as to rest his belly against it, ‘the brothers Stercza are to blame for the disturbance in town. The brothers Stercza are to blame for the material damage and bodily injuries. The brothers Stercza are to blame for the grave injury to and – God forbid – the death of the Very Reverend Prior. They, and they alone. And what happened to Nicolaus of Stercza was a . . . mishap. Thus shall we present it to the duke on his return. Agreed?’

‘Agreed.’

‘Consensus omnium.’

‘Concordi voce.’

‘But were Reynevan to appear anywhere,’ Father Gall added a moment later, ‘I advise seizing him quietly and locking him up here, in our town-hall gaol. For his own safety. Until the matter blows over.’

‘It would be well to do so swiftly,’ added Łukasz Friedmann, examining his rings one last time, ‘before Tammo of Stercza gets wind of the damnable business.’

As he left the town hall and headed straight into the darkness of Saint John’s Street, the merchant Hofrichter glimpsed a movement on the tower’s moonlit wall, an indistinct, moving shape a little

below the windows of the town trumpeter, but above the windows of the chamber where the meeting had just finished. He stared, shielding his eyes from the somewhat blinding light of the lantern carried by his servant. What the Devil? he thought and crossed himself. What’s creeping across the wall up there? An owl? A swift? A bat? Or perhaps . . .

Jan Hofrichter shuddered, crossed himself again, pulled his marten-fur calpac down over his ears, wrapped his coat around him and set off briskly home. Thus he didn’t see a huge wallcreeper spread its wings, fly down from the parapet and noiselessly, like a nightly spectre, glide over the town’s rooftops.

Apeczko of Stercza, Lord of Ledna, didn’t like visiting Sterzendorf Castle. There was one simple reason: Sterzendorf was the seat of Tammo of Stercza, the head and patriarch of the family – or, as some said, the family’s tyrant, despot and tormentor.

The chamber was airless. And dark. Tammo of Stercza didn’t let anyone open the windows for fear of catching cold, or the shutters, because light dazzled the cripple’s eyes.

Apeczko was hungry and covered in dust from his journey, but there was no time either to eat anything or to clean himself up. Old Stercza didn’t like to be kept waiting. Nor did he usually feed his guests. Particularly members of the family.

So Apeczko was swallowing saliva to moisten his throat – he hadn’t been given anything to drink, naturally – and telling Tammo about the events in Oleśnica. He did so reluctantly, but he had no choice. Cripple or not, paralysed or not, Tammo was the family patriarch. A patriarch who didn’t tolerate defiance.

The old man listened to the account, slumped on a chair in his familiar, bizarrely twisted position. Misshapen old fart, thought Apeczko. Bloody mangled old bugger.

The cause of the condition of the Stercza family’s patriarch was neither fully understood nor common knowledge. One thing wasn’t in doubt – Tammo had suffered a stroke after a fit of rage. Some claimed that the old man had become furious on hearing that a personal enemy, the hated Konrad, Duke of Wrocław, had been anointed bishop and become the most powerful personage in Silesia. Others were certain the ill-fated outburst was the result of his mother-in-law, Anna of Pogarell, burning Tammo’s favourite dish – buckwheat kasha with fried pork rind. No one would ever know what really happened, but the outcome was evident and couldn’t be ignored. After the accident, Stercza could only move his left hand and foot – and clumsily at that. His right eyelid drooped permanently, glutinous tears oozed ceaselessly from his left, which he occasionally managed to lift, and saliva dribbled from the corner of his mouth, which was twisted in a ghastly grimace. The accident had also caused almost complete loss of speech, giving rise to the old man’s nickname: Balbulus. The Stammerer-Mumbler.

The loss of the ability to speak hadn’t, however, resulted in what the entire family had hoped for – a loss of contact with the world. Oh, no. The Lord of Sterzendorf continued to hold the family in his grasp and terrorise everybody, and what he wanted to say, he said. For he always had to hand somebody who could understand and translate his gurgling, wheezing, gibbering and shouts into comprehensible speech. That person was usually a child, one of Balbulus’s countless grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

This time, the interpreter was ten-year-old Ofka of Baruth, who was sitting at the old man’s feet and dressing a doll in colourful strips of rag.

‘Thus,’ Apeczko finished his account, cleared his throat and moved on to his conclusion, ‘Wolfher asked me through an emissary to inform you that he will deal swiftly with the matter. That Reinmar of Bielawa will be seized on the Wrocław road and punished. But for the present, Wolfher’s hands are tied because the Duke of Oleśnica is journeying with his entire court and diverse eminent clergymen, so there is no way to pursue him. But Wolfher vows to seize Reynevan and claims he can be entrusted with the family’s honour.’

Balbulus’s eyelid twitched and a dribble of saliva trickled from his mouth.

‘Bbbhh-bhh-bhh-bhubhu-bhhuaha-rrhhha-phhh-aaa-rrh!’ reverberated through the chamber. ‘Bbb . . . hrrrh-urrrhh-bhuuh! Guggu-ggu . . .’

‘Wolfher is a bloody moron,’ Ofka of Baruth translated in her high, melodious voice. ‘An idiot I wouldn’t even trust with a pail of puke. And the only thing he’s capable of seizing is his own

prick.’

‘Father—’

‘Bbb . . . brrrh! Bhhrhuu-phr-rrrhhh!’

‘Silence,’ translated Ofka without raising her head, busy with her doll. ‘Listen to what I say. To my orders.’

Apeczko waited patiently for the wheezing and croaking to finish and then for the translation.

‘First of all, Apecz,’ Tammo of Stercza ordered via the little girl’s mouth, ‘you will establish which of the women in Bierut.w was charged with supervising the Burgundian. She obviously didn’t realise the true aim of those charitable visits to Oleśnica or alternatively was in league with the harlot. Give that woman thirty-five sound lashes with a birch on her naked arse. Here, in my chamber, in front of my eyes, that I might at least have a little diversion.’

Apeczko of Stercza nodded. Balbulus coughed, wheezed and slobbered all over himself, then grimaced dreadfully and gaggled.

‘I order the Burgundian, meanwhile, to be taken from the Cistercian convent in Ligota, where I know she is in hiding,’ translated Ofka, tidying her doll’s oakum hair with a small comb, ‘even if you have to storm it. Then imprison the trollop among monks favourably disposed towards us, for example—’

Tammo abruptly stopped stammering and gobbling, his wheezing caught in his throat. Apeczko, pierced by the old man’s bloodshot eye, saw that he had noticed his embarrassed expression.

That he understood. Th at it was impossible to hide the truth any longer.

‘The Burgundian escaped from Ligota,’ he stammered. ‘In secret . . . No one knows whither. Busy with the pursuit of Reynevan . . . they – we – allowed her to escape.’

‘I wonder,’ Ofka translated after a long, pregnant silence, ‘I wonder why this doesn’t surprise me at all. But since it is so, let it be. I won’t bother myself with the whore. Let Gelfrad deal with the matter on his return. He can handle it himself, whether or not he’s a cuckold. It’s nothing new in this family, actually. It must have happened to me, for it can’t be possible that such fools sprang from my own loins.’

Balbulus coughed, wheezed and choked for a while. But Ofka didn’t translate, so it couldn’t have been speech, just ordinary coughing. Th e old man fi nally took a breath, grimaced like a demon and struck his cane against the floor, then gurgled horribly. Ofka listened, sucking the end of her plait.

‘But Nicolaus was the family’s hope,’ she translated. ‘Was of my blood, the blood of the Sterczas, not the dregs of the Devil knows what mongrel couplings. So the killer will have to pay for Nicolaus’s spilled blood. With interest.’

Tammo banged his cane against the floor again. It fell from his shaking hand. The Lord of Sterzendorf coughed and sneezed, spraying saliva and snot around. Hrozwita of Baruth, Balbulus’s daughter and Ofka’s mother, who was standing alongside, wiped his chin, picked up the cane and pressed it into his hand.

‘Hgrrrhhh! Grhhh . . . Bbb . . . bhrr . . . bhrrrllg . . .’

‘Reinmar of Bielawa will pay me back for Nicolaus,’ Ofka translated unemotionally. ‘He will pay, as God and all the saints are my witnesses. I will lock him up in a dungeon, in a cage, in a chest like the one the Duke of Głogow cast Henry the Fat into, so small he won’t even be able to scratch himself, with one hole for food and another directly opposite. And I’ll keep him like that for half a year. And only then go to work on him. And I’ll bring a torturer all the way from Magdeburg, because they have excellent men there, not like the ones here in Silesia, where the rascal expires on the second day. Oh, no, I’ll get hold of a master who’ll devote to Nicolaus’s killer a week. Or two.’

Apeczko Stercza swallowed.

‘But to do that,’ Ofka continued, ‘we must seize the adulterer. Which demands intelligence. Wits. Because the adulterer is no fool. A fool wouldn’t have graduated from Prague, or ingratiated himself with the Oleśnica friars, or have so ably seduced Gelfrad’s French wife. With a crafty one like that, it’s not enough to chase up and down the Wrocław road like an idiot, making a fool of oneself. Giving the affair renown that will serve the rake – and not us.’

Apeczko nodded. Ofka looked at him and sniff ed and wiped her little snub nose.

‘The adulterer,’ she translated on, ‘has a brother, residing on an estate somewhere near Henrykow. It’s quite likely he’ll seek shelter there. Perhaps he already has. Another Bielawa, before he died, was a priest at the Wrocław Collegiate, so it’s conceivable the rascal will want to hide with another rascal. I mean to say with His Excellency, the Most Reverend Bishop Konrad, that old soak and thief!’

Hrozwita of Baruth once again wiped the old man’s chin, which was covered in snot after his furious outburst.

‘Furthermore, the rake has acquaintances among the monks of the Monastery of the Holy Ghost in Brzeg, in the hospice. Our sly boots may have headed there, to surprise and mislead Wolfher. Which isn’t too difficult, in any case. Finally, the most important thing. Listen carefully, Apecz. It’s certain that our adulterer will want to play the trouveur, pretend to be some sort of Lohengrin or Lancelot. He will want to contact the Frenchwoman. And we will most likely catch him there, in Ligota, like a dog with a bitch in heat.’

‘Why in Ligota?’ Apeczko dared to ask. ‘For she—’

‘Has fled, I know. But he doesn’t.’

The old fart’s soul, thought Apeczko, is even more twisted than his body. But he’s as cunning as a fox. And, to give him his due, he knows a great deal. Knows everything.

‘But to achieve what I have just ordered,’ Ofka translated into comprehensible language, ‘you’re not much bloody use to me – you, my sons and nephews, blood, apparently, of my blood and bone of my bone. Therefore, you will hasten as quickly as you can to Niemodlin, and then to Ziębice. When you get there . . . Listen carefully, Apecz. You will find Kunz Aulock, called Kyrie-eleison. And others: Walter of Barby, Sybek of Kobylagłowa and Stork of Gorgowice. You will tell them that Tammo Stercza will pay a thousand Rhenish guilders for the capture of Reinmar of Bielawa alive. A thousand – remember.’

Apeczko swallowed at each name, for they were the names of the worst thugs and killers throughout Silesia, scoundrels with neither honour nor faith. Prepared to murder their own grandmothers for three skojeces, never mind the astonishing sum of a thousand guilders. My guilders, thought Apeczko crossly. Because that ought to be my inheritance when that damned cripple finally kicks the bucket.

‘Do you understand, Apecz?’

‘Yes, Father.’

‘Then begone, off with you. Out of here, to horse, carry out my orders.’

First, thought Apeczko, I’ll head towards the kitchen, where I’ll eat my fill and drink enough for two, you stingy old bugger. And then we’ll see.

‘Apecz.’

Apeczko Stercza turned around. And looked. But not at Balbulus’s contorted, fl ushed face, which seemed to him, for the first time here in Sterzendorf, to be unnatural, out of place. Apeczko looked into little Ofka’s huge, nut-brown eyes. At Hrozwita, standing behind

his chair.

‘Yes, Father?’

‘Do not let us down.’

But perhaps it isn’t him at all? The thought flashed through his mind.Perhaps it’s a corpse sitting on this chair, a half-dead carcass with its brain utterly eaten up by paralysis? Perhaps . . . it’s them? Perhaps it’s the women – girls, maidens and matrons – who rule at Sterzendorf?

He quickly drove away the preposterous thought.

‘I won’t, Father.’

Apeczko Stercza had no intention of hurrying to carry out Tammo’s orders. He walked briskly to the castle kitchen, murmuring angrily, where he demanded everything the said kitchen had to offer. Let the cripple lord it in his chamber upstairs; outside, executive power belonged to somebody else. Outside the chamber, Apeczko of Stercza was master, and he demonstrated it as soon as he entered the kitchen. A dog earned a kick and bolted, howling. A cat fled, deftly dodging the large wooden spoon thrown at it. The maids flinched as a cast-iron cauldron slammed down on the stone floor with a dreadful bang. Th e most sluggish maid was hit on the back of the neck and called a whorish clod. Th e serving boys learned all sorts of things about themselves and their parents, and several made the close acquaintance of their master’s fist, as hard and heavy as a lump of iron. A servant who needed to be told twice to bring wine from the master’s cellar received such a kick that he lurched forward onto hands and knees.

Soon after, Apeczko – SirApeczko – was sprawled on his chair, greedily chewing great mouthfuls of roast venison, fatty pork ribs, a huge ring of blood pudding, a hunk of dried Prague ham and several pigeons boiled in broth, accompanied by a whole loaf of bread as large as a Saracen’s buckler. Washed down, naturally, with the best Hungarian and Moldavian wines, which Balbulus kept for his own personal use. He tossed bones on the ground like a lord of the manor, spitting, belching and glowering at the fat housekeeper, just waiting for her to give him an excuse.

The old bugger, the old fart, the paralytic orders me to call him ‘father’ when he’s only my uncle, my father’s brother. But I must put up with it. For when he fi nally turns up his toes, I, the eldest Stercza, will at last become head of the family. Th e inheritance, of course, will have to be divided up, but I shall be head of the dynasty. Everybody knows it. Nothing will hinder me. Nothing will stop me . . .

What might hinder me, thought Apeczko, swearing under his breath, is this furore with Reynevan and Gelfrad’s wife. What may hinder me is a family feud making me fall foul of the Landfriede laws governing family feuds. Hiring thugs and killers may hinder me, as might the noisy pursuit, incarceration in a dungeon, ill-treatment and torture of a lad who’s kin of the Nostitzes, related to the Piasts and a vassal of Jan of Ziębice. And Konrad, Bishop of Wrocław – whose dislike of Balbulus is mutual – is just waiting for the first opportunity to give the Sterczas what for. Not good, not good, not good.

And to blame for all of this, Apeczko suddenly decided, picking his teeth, is Reynevan, Reinmar of Bielawa. And he shall pay for it. But not in a way that would incite the whole of Silesia. He shall pay in an ordinary way, quietly, in the dark, with a knife in the ribs. When – as Balbulus guessed right – he appears in secret at the Cistercian sisters’ convent in Ligota, beneath his lover’s window. One thrust of a knife and he’ll land plop in the Cistercians’ carp pond. And hush! The carp won’t let on.

On the other hand, one cannot utterly ignore Balbulus’s instructions, if only because the Mumbler usually checks whether his orders are executed by giving the same orders to not one, but several persons.

What to do, by the Devil?

Apeczko thrust a knife into the table with a thud and drained his beaker in one draught. He looked up and met the gaze of the fat housekeeper.

‘What are you staring at?’ he growled.

‘The senior master has recently stocked up with some excellent Italian wine,’ said the housekeeper calmly. ‘Shall I have it drawn, Your Grace?’

‘Indeed.’ Apeczko smiled in spite of himself and felt the woman’s calm soothing him, too. ‘Indeed, please do, I shall taste what has been maturing in Italy. And please send a boy to the watchtower, have him bring me a half-decent horseman with his wits about

him. Someone who’s capable of delivering a message.’

‘As you wish, Your Grace.’

Hooves thudded on the bridge. The messenger hastening away from Sterzendorf looked back and waved at his woman, who was bidding him farewell from the embankment with a snow-white kerchief. And suddenly caught sight of movement on the moonlit wall of the watchtower, a vague moving shape. What the Devil?He thought. What’s creeping about there? An owl? A swift? A bat? Or perhaps . . .

The messenger muttered a spell to protect him from magic, spat into the moat and spurred on his horse. The message he was carrying was urgent, and the lord who had sent it cruel.

So he didn’t see a huge wallcreeper spread its wings, fly down from the parapet and noiselessly, like a nightly spectre, glide over the forests eastwards, towards the Widawa Valley.

Sensenberg Castle, as everybody knew, had been built by the Knights Templar, and not without reason had they chosen that exact location. Looming above a jagged cliff face, its summit had been a place of worship to pagan gods since time immemorial, where, so the stories said, the people of the ancient Trzebowianie and Bobrzanie tribes offered the gods human sacrifices. During the twelfth century, when the circles of round, moss-covered stones hidden among the weeds were all that remained of the pagan temple, the cult continued to spread and sabbath fires still burned on its summit in spite of several bishops’ threats of severe punishments for anyone who dared celebrate the festum dyabolicum et maledictumat Sensenberg.

But in the meantime, the Knights Templar arrived. They built their Silesian castles, menacing, crenelated miniatures of the great Syrian Templar fortresses, erected under the supervision of men with heads swathed in scarves and faces as dark as tanned bull’s hide. It was no accident that they always located their strongholds in the holy places of ancient, vanishing cults like Sensenberg.

Then the Knights Templar got what was coming to them. Whether it was fair or not, there is no point arguing over it; they met their end, and everybody knows what happened. Their castles were seized by the Knights Hospitaller and divided up between the rapidly expanding monasteries and the burgeoning Silesian magnates. Some, in spite of the power slumbering at their roots, very quickly became ruins. Ruins which were avoided. Feared.

Not without reason.

In spite of escalating colonisation, in spite of settlers hungry for land arriving from Saxony, Thuringia, the Rhineland and Franconia, the mountain and castle of Sensenberg were still surrounded by a strip of no man’s land, a wilderness only entered by poachers or fugitives. And it was from those poachers and fugitives that people first heard stories about extraordinary birds and spectral riders, about lights flashing in the castle’s windows, about savage and cruel cries and singing, and about ghastly music which appeared to

spring up from nowhere.

There were those who did not believe such stories. Others were tempted by the Templar treasure that was said still to lie somewhere in Sensenberg’s vaults. And there were downright nosy and restless individuals who had to see for themselves. They never returned.

That night, had some poacher, fugitive or adventurer been in the vicinity of Sensenberg, the mountain and castle would have given cause for further legends. A storm was approaching from far beyond the horizon and flashes of lightning flared in the distance, so far away you couldn’t even hear the accompanying rumble of thunder. And suddenly, the bright eyes of the windows blazed in the black monolith of the castle, framed against the flashes in the sky.

For inside the apparent ruin stood a huge, stately hall with a high ceiling. Th e light from candelabras and torches in iron cressets accentuated the frescos on the bare walls portraying religious and knightly scenes. There was Percival, kneeling before the Holy Grail, and Moses, carrying the stone tablets down from Mount Sinai, and Jesus, falling beneath the cross for the second time. Their Byzantine eyes gazed down upon the great round table and the knights in full armour and hooded cloaks sitting around it.

A huge wallcreeper flew in through the window on a gust of wind.

The bird wheeled around, casting a ghastly shadow on the frescos, and alighted, puffi ng up its feathers, on one of the chairs. It opened its beak and screeched, and before the sound had died away, not a bird but a knight was sitting on the chair, dressed in a cloak and hood, looking almost identical to the others.

‘Adsumus,’ the Wallcreeper intoned dully. ‘We are here, Lord, gathered in Your name. Come to us and be among us.’

‘Adsumus,’ the knights encircling the table repeated in unison.‘Adsumus! Adsumus!’

The echo spread through the castle like a rumbling thunderclap, like the sound of distant battle, like the booming of a battering ram on a castle gate. And slowly faded among the tenebrous corridors.

‘May the Lord be praised,’ said the Wallcreeper, after the echo fell silent. ‘Th e day is at hand when all His foes will be reduced to dust. Woe betide them! Th at is why we are here!’

‘Adsumus!’

‘My brothers, providence is sending us another chance to smite the Lord’s foes and to beset the enemies of the faith,’ the Wallcreeper intoned, lifting his head, his eyes gleaming with the reflected light of a flame. ‘The time has come to deliver the next blow! Remember this name, O brothers: Reinmar of Bielawa. Reinmar of Bielawa, called Reynevan. Listen . . .’

The hooded knights leaned in, listening. Jesus, falling beneath the cross, looked down on them from the fresco, and there was endless human suffering in his Byzantine eyes.

The Tower of Fools is out 27th October 2020 and is available to pre-order now. Get your copy here.